Yesterday L.A. Opera announced that ticket sales for the Ring cycles are not meeting expectations. Their overall budget is falling another million dollars short. Maybe a million and a half. Their excuses include the volcano in Iceland. Personally I think the Gods must be angry. (Read the financial story at the L.A. Times)

The Opera is also holding Ring Festival L.A., a favorite topic at Mixed Meters. You can read about it here and here and here and here and here. Or not.

This post is my contribution to Ring Festival L.A. They're not likely to be thrilled. It is inspired by the work of one California composer who, almost 50 years ago, dealt conceptually with the problem of Wagner's Ring. I gather that his idea was never completely realized in sound. Maybe this is the first time.

BACKGROUND

From 1962 through 1966 there was a flowering of avant garde music right here in California at a place called the San Francisco Tape Music Center. It was a labor of love by a small group of young composers who existed in the vortex of counter-culture energy and revolution which, only a few years later, would give us Flower Power, the Summer of Love and the Grateful Dead.

One of the founders of the SFTMC was Ramon Sender. As a student I remember reading how Sender had used a tape recorder to reduce all of Wagner's Ring to four short clicks. I assumed he would have done this by recording at a very slow speed and playing the tape back very fast. Unfortunately, I don't remember where I read this; it was just a short reference. Clearly the idea stuck in my brain. (Update: See note from Sept. 2012 below.)

Recently I discovered a fascinating book called The San Francisco Tape Music Center, 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-Garde edited by David W. Bernstein. It includes interviews with the principals of SFTMC: composers, performers, equipment designers, dancers and light show artists. Here's part of the interview with Ramon Sender. He is discussing a very early three-head Ampex tape recorder:

I discovered that there was a tension adjustment on the reels. You could actually put it in "record" mode, not turn on the track to travel, but just put on the tension adjustment, and the tape would creep very slowly. That was when I started doing things like putting all of a Wagner opera on an eighth of an inch of tape. I thought, wow I could sell this to conservatory students to help them do their assignments. You want to listen to the Ring of the Nibelung? Here, you can do it in a quarter of a second.Fascinating! Of course it's not as simple as he makes it seem. First of all, tape moving that slowly on an analog tape recorder, the equivalent of 1 inch per day, would have no usable signal recorded on it. When playing it back there would be all noise, a signal to noise ratio of zero.

Given the limited frequency response of his equipment, Sender's comment about helping students is an obvious joke. In my mind, however, it is an admirable goal. The students probably didn't really want to listen to the Ring in the first place. I say hooray for audio Cliff's notes.

Sender is also careful to say he did this only with "a Wagner opera" not with the entire Ring. My best guess is that reducing the Ring of the Nibelung to four clicks, as reported in that book I read, was always a concept. Sender's conceptual piece is easy to imagine and very communicative artistically, but at that time it was probably not worth the energy to turn it into actual audio.

As you can well imagine, I really like Ramon Sender's idea of compressing the Ring until it simply evaporates into a whiff of meaningless noise. The problem of Wagner's excessively long music is solved.

THE ENTIRE RING IN FOUR CLICKS

In the sixties creative forward-looking musicians worked with early analog tape recorders and even earlier analog synthesizers and dreamed of an entirely new type of music. In nearly every respect the music they dreamed up was completely unlike Wagner.

They were inspired by the new electronic tools at their disposal. Maybe in their wildest, wildest dreams they imagined analog equipment would someday be supplanted by digital devices. Could they have imagined that digital technology would become so ubiquitous and so portable and so powerful that anyone could accomplish the most complex audio editing almost anywhere. If they did imagine that, then they probably didn't believe they'd live to see the day. Turns out, they did.

In 2010 speeding up the entire Ring until it becomes four quick clicks is a rather trivial exercise. I did it - and so could you - using the free program Audacity (highly recommended). I repeatedly doubled the speed of each opera. Just as with an analog tape machine, each doubling halves the length of the music and doubles the frequency, raising the pitch by one octave. After about six octaves all resemblance to the original music disappears and only noise created by the inherent limitations of the equipment remains.

I repeated this process sixteen times. The final length is 1/1024th of the original. Each opera lasts about a quarter of a second. You'll be able to hear all four clicks in one second. Theoretically the notes are sixteen octaves higher than the original. With perfect fidelity the lowest audible frequency would have been transformed to over a half million cycles per second. That is in the range of AM radio. In reality nothing of Wagner remains. Instead of a time-saving subliminal way listen to Wagner, this process has simply removed all the content from his music. Another problem solved.

Click here once to hear the entire Ring cycle as four clicks. It'll only take a second.

THE ENTIRE RING, AT PITCH, IN SEVEN MINUTES

Recreating the tricks of old analog tape equipment is far from the only use for digital audio. You can also manipulate sounds in ways which were inconceivable with analog equipment. For instance, with digital audio you can change the pitch of music without changing the duration. A good example of this, from pop music, would be AutoTune. You can also change speed without changing pitch. Making music slower is the idea behind 9 Beet Stretch which turns a seemingly interminable piece into an unbearably interminable one.

And, by making music faster, you can compress all of Wagner's Ring into a few minutes leaving mere hints of the original content. That's what I've done. Naturally a tremendous amount of musical information has been lost but you can still hear Wagner in there somewhere.

For this realization I did seven halvings of the length of the Ring, making it 1/128th the length, keeping the pitches unchanged. The result remains well within the frequency response of modern technology. You can identify the occasional tonality, distinguish voices and instruments, hear loud and soft sections and generally get a feel for the flow of the music. But it remains gobbelty-gook. No way to solve that problem.

Click here to listen to the entire Ring cycle in seven minutes.

THE PROBLEM OF WAGNER'S RING

Wagner's Ring is not a "problem" for opera queens and ring nerds. More power to them. But it can be a huge issue for an avant garde composer trying to face the unknown future of music who resents being pursued from behind by the continuing popularity and influence of this massive and vicious Romantic era monster. Not all composers acknowledge the problem; not all composers are interested in the future. Many are happy to imitate Wagner as best they can in hopes of getting their own operas performed. Or of getting work writing movie scores.

Actually, I suspect most composers are simply oblivious. They don't care about Wagner at all. Much more power to them.

I'd like to end with a quote about Wagner's excessive influence as expressed by a composer who lived much closer to Wagner's time and is now regarded as one of the all-time greatest creative musical minds. It was a time when Wagner was at the peak of his musical importance and the problem of finding a new non-Wagnerian future was most acute.

The thing, then, is to find what comes after Wagner's time but not after Wagner's manner.Claude Debussy said this in his letters. I found it quoted in Peter Yates' 1967 book Twentieth Century Music.

=-=-=-=-

After Leslie listened to the four clicks she remarked that some people might find even this version too long.

The transformational idea behind multiple octave changes reminds me of Frank Zappa's Big Note.

My own deconstruction of Wagner - or at least his one and only real contribution to pop culture - is called Wagner and Schubert Have Intercourse.

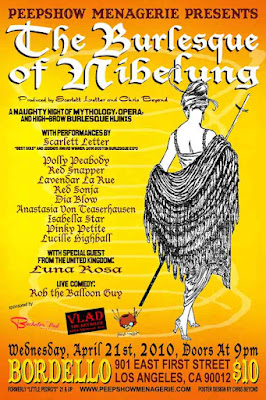

Read about Burlesque of Nibelung which apparently happened a little over a month ago in downtown L.A. Billed as "a naughty night of mythology, opera and high-brow burlesque hi-jinks", I suspect it's another unauthorized Ring Festival L.A. celebration.

ADDENDUM: I confess, the "Four Clicks" are not so much clicks as bursts of white noise. But I distinctly remember that early book reference called the sounds "clicks" and I have kept the term.

September, 2012 ADDENDUM: Thanks to Tom Service of the Guardian for linking to this post.

My original encounter with the idea of reducing Wagner, including the word clicks, is now available online. It was from an article by Pauline Oliveros entitled Some Sound Observations, published originally in issue 3 of Source: Music of the Avant-Garde, 1966-1973 (page 136 of a 2011 reprint by UC Press and readable on Google.) Here's what she wrote:

One's ideas about music can change radically after listening to recorded works at fast forward or rewind on a tape recorder. Ramon Sender arranged Wagner's Ring Cycle by a series of re-recordings at fast forward to four successive clicks.

3-Head Tags: Richard Wagner. . . Ring of the Nibelung. . . LA Opera. . . Ring Festival LA. . . Ramon Sender. . . San Francisco Tape Music Center. . . analog tape recorder

6 comments :

Hal Freedman's 1982 Ring Précis reduces the four music dramas to four and a half minutes, at pitch.

Thanks, Anon. Never heard of Hal Freedman and there's very little easy-to-find info on the web. I did learn that his Ring piece was done in 1974 and released in 1982. Apparently the methodology was to divide the four operas into about 200 short sections and overlap them so they're all sounding at once.

"One of the founders of the SFTMC was Ramon Sender. As a student I remember reading how Sender had used a tape recorder to reduce all of Wagner's Ring to four short clicks. I assumed he would have done this by recording at a very slow speed and playing the tape back very fast. Unfortunately, I don't remember where I read this; it was just a short reference. Clearly the idea stuck in my brain."

I had never heard of Ramon Sender until a few years ago when a client of mine referred to her old boyfriend, one of the founders of the SF Tape Music Ctr, & that was in fact Ramon. The idea of time warping existing music must have been around, in the aether I suppose, because some time in the mid or late 1970's I did exactly the same thing (believing it to be an original idea,) to reduce the duration of a 23 minute Pink Floyd piece to about 20 seconds, which found its way into then back out of a tape piece of mine. The result was a whole lot less interesting than the idea.

When people refer to "experimental" music I always have an image of failure in my mind. The successful pieces aren't experiments, they are the result of methodologies which are demonstrably effective. The experiments are the things we try & discard along the way to making something which really works, which is then no longer an experiment. Shortening a well known piece of music via tape speed manipulation, with the hope of maintaining some of the original music's interest, vitality, importance or other quality is an experiment, which unfortunately sounds like shit.

SF

Scott, an experimental piece that works well is no longer referred to as "experimental" and, gradually, the composer forgets that he or she may not have known exactly how it was going to turn out.

Yes, the idea was around. Ramon Sender had the idea in the early sixties, not the seventies, and may well have thought it up himself.

These Ring manipulations are process music - a style of composition which was pretty new in the seventies and (alas) is still quite prevalent. I have great issues with it now, feeling quite cheated if the entire content of a piece is revealed in the first minute or so. I like my music to have at least surprises in it.

I agree, the 7-minute Ring reduction does sound like shit. Did you notice I didn't claim it as a piece of my own?

I smiled through the seven-minute version, because it was downright funny. (I think I recognized "Forrest Murmurs" when it fleetingly flitted by, but I probably just imagined it.)

As for it "sounding like shit," I've heard LOTS worse, occasionally during concerts of NeW MuSiC.

I was a student of the Advanced Studies Program at St. Paul's School in 1975, and Hall Freedman was my music Intern. He played the Ring Precis for us, -so I've heard it. Being a novice at the time, all I remember is that it sounded to me like someone kicking a metal garbage can around. 22 years later, I sang in the Seattle Opera Gotterdammerung Chorus. One of life's little ironies.

Post a Comment