The musical style called minimalism has done a great disservice to the music of William Kraft. Long waves of music history do not carry every composer along with identical speed and energy.

And several of the most essential musical elements of Kraft's music have not found congenial support in our current minimalist ecology.

I came to that conclusion Monday evening while listening to the first of several concerts devoted to

Kraft's cycle of chamber works called Encounters. Jerry Zinser wrote this excellent review about what actually happened. You should read that since I'm not going to cover the details.

The concert was downtown at Zipper Hall - a fine focus point for our naturally uncentered new music community - even if its interior decoration does remind me of a birthday cake. The entire Encounters cycle will require several concerts. It is being produced by

Southwest Chamber Music who will record the entire series as well. That's important.

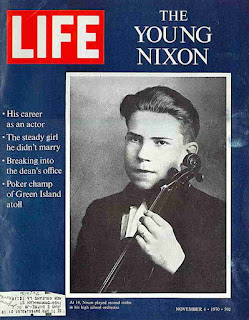

Kraft grew up in Southern California and obtained his musical education in a large eastern metropolis.

He has been a leading figure in Los Angeles' new music scene pretty much since he joined the Los Angeles Philharmonic as a percussionist back in 1955. Yes, over fifty years ago. He's now 84 and going strong.

Eventually he became timpanist, associate conductor, and then composer-in-residence of the orchestra - founding

the Phil's New Music Group. He was active in the Monday Evening Concerts during the halcyon Stravinsky days and in its

current post-LACMA reincarnation. His last job was holding down the Corwin Chair of Music Composition at the University of California Santa Barbara.

Now he's retired and he continues to compose - sometimes complaining of overwork.

Here's his bio at the website of his publisher Theodore Presser.

I met Bill in the mid-70s when he was a guest teacher in my graduate composition seminar. I remember gathering around him on the floor while he sang poly-rhythms from an Elliott Carter score the Phil was performing.

I've worked for Bill as music copyist for well over 20 years, starting right after I left Zappa. That's longer than any other of my clients.

He and his wife Joan live not far from us and lately he and I have started getting together just to talk about music.

I know a lot about his compositions in that curious way that a music copyist studies scores.

And there are a lot of other things I don't know - in that not so curious way a copyist ignores the obvious while obsessing over details.

And believe me -

there are a lot of details in William Kraft's music. He rarely writes a repeat of anything without specifying a variation of some aspect of the sound. For example, on Monday at the beginning of Encounters III, I was amused to watch the trumpet player change his mute for each of the first four long notes. In many ways he completely eschews the idea of repetition in music.

Kraft carries the art of delicate musical coloration to new heights when he writes for a multiple percussion setup - meaning one player surrounded by (and sometimes hidden behind) a specific "architecture" of percussion. A setup is usually anchored by a mallet instrument (probably a vibraphone) plus various ranks of wood, metal or skin instruments (graduated groupings of similar sounds.) The idea is to allow many different sounds to be alternated quickly or combined simultaneously.

This adds an element of "choreography" to Bill's writing. Different than the stylized choreography I witnessed

in the taiko ensemble on Sunday,

the percussionist in a Kraft work must carefully plan every movement in advance. Bill might specify which style of mallet the player will hold in each hand, when to flip the mallets and use the other end. Since the choice of mallet can greatly change a sound Bill gives many instructions on their use. Padded tables for easy mallet access is an essential element any Kraft setup. The trick for the performer is to prepare for the next sound while the last one is still ringing.

I enjoyed watching and hearing several specific percussion techniques that are typically Kraftian (David Raksin would have called them "Krafty"). Examples include:

- bending a note on a vibraphone, usually a fixed pitch instrument.

- Bunker Trill Slow, a unique vibraphone "wah wah" effect created by fiddling with the internal moving parts.

- cluster mallets - designed to hit a dozen or more vibraphone or chime notes simultaneously.

- And a truck suspension spring which makes a fine gong.

These sounds take time to appreciate. Their position in time is critical to keep them from blurring together and obscuring one another.

I feel that Bill's music is often played too quickly - not allowing a listener the chance to appreciate or even to distinguish the constantly shifting sonorities. Small constellations of notes, like sparks from a firework, cannot be well appreciated if they are played as a musical "lick".

I have hopes that the recording of the Encounters series will highlight this pleasant, timeless, floating quality.

Of course a recording will also remove the visual element - and I look forward to that as well. In Encounters I for percussion and tape, during a tape interlude, the player mutes specific individual bars of the vibraphone with C clamps and then further mutes the entire instrument with a blanket. I suspect that the audience was more involved watching this process and wondering what would happen next than they were with listening to the taped sounds.

So what does all this have to do with minimalism, the reigning musical aesthetic of our time? Nothing. Absolutely nothing at all.

So what does all this have to do with minimalism, the reigning musical aesthetic of our time? Nothing. Absolutely nothing at all. That's my point.

Many of these musical ideas, so important in the music of William Kraft, were discarded by the minimalists. In the multiple exact repetitions, phasing, process-controlled forms and aggressive, inflexible timbres of so much minimal music it just didn't make sense to wait around to hear the overtones of a truck spring fade away. In our rush to hear music that goes du-ee du-ee du-ee du-ee du-ee, many of us seemed to forget that other solutions hold great beauty.

Kraft's activities as a composer began in earnest in the 1960's about the same time as the first rumblings of minimalism. Terry Riley's In C predates the start of the Encounters cycle by several years. Since that time Minimalism has come and ... er, well - it hasn't gone yet has it?

But during the same years, the heyday of minimalism, William Kraft, in his chosen role as a composer, has honed his ... craft.

He's created a body of work that deals with time itself on his own terms while not adhering to the fashions of the time. And because of that I think he deserves a little more respect.