This thin book, Terry Riley's In C by Robert Carl, is interesting mostly for the information about the composer's early life and the events surrounding the creation, performance and initial recording of his famous 1964 work. Carl's musical analysis and reviews of various recordings are less involving.

In C is a genuine classic piece of music of our time. By "our" I mean baby boomers. In those days when many of us encountered this style of music for the first time ("minimalism" wasn't the default term yet), it seemed like an endless open vista wherein anything might be possible.

In C was hugely important in my own personal development as a musician. You can no longer hear this in my current music but it was quite obvious back in my "first compositional period" (before I temporarily gave up writing in the early 90's).

In the 70's, when I was studying weird new music at CalArts, I used to come home at night exhausted from music by the likes of Stockhausen, Cage or Carter and relax by listening to the original Columbia recording of In C with the little electronic whoosh marking the split between side A and side B. Some evenings I listened to it all the way through twice or three times, all 40-some minutes of it.

Of course being a little stoned didn't hurt - but wasn't required. The music had a positive, heady power; so much energy. It carried me along. It was completely different from the dry new music which dominated my graduate education. More importantly I was totally amazed by two important qualities of In C: its structural simplicity and its social egalitarianism. I still am.

SIMPLE

In C is actually a kind of orchestra piece. Riley suggests about 35 players as the optimum number, although it has been done with many fewer or many more. In an interview he said that it might be played solo if the right player could be found. Good luck with that. It works well as a chamber piece for seven or eight very busy players.

With big ensembles In C challenges the notion that large symphonic works need huge over-notated scores filled with inaudible precision. The entire score fits on one letter size sheet of paper. A conventional orchestra score of similar length might have as many as 200 densely packed pages.

Obviously this seems more important to a person who has spent his entire career dealing with printed musical notation than it does to you. If such simplicity had become the norm rather than a single exception I might have had to find myself a different line of work.

Riley's composition allows only a few written notes to produce a highly complex texture every bit the equal of more precisely written pieces. It comes out differently every time - but it is never so different that you can't identify it immediately. This simplicity is a worthy and all-too-rare quality of contemporary music.

Originally the instructions on how to play that one small sheet of music were handed down verbally from musician to musician. Years later Riley added some text instructions codifying the performance practice - although he still seems pretty loose about the rules.

Here is the full orchestra score of In C. You can download a better looking pdf along with the instructions from Otherminds.

EGALITARIAN

The other important, mind-blowing idea which In C represented to me is its complete revolution in the social structure of the orchestra.

In a conventional orchestra the most-important person (i.e. the "conductor") dictates behavior from above. He stands alone, elevated on a podium. Meanwhile, down among the players, there is a formal pecking order. For example, the principal players, the ones who get the solos, are ranked higher than the garden variety section players. They get paid more too.

Of course this hierarchical arrangement is endemic throughout our society. Most people experience it constantly - at work, in school or in a family. Orchestra hierarchy bothered me a lot when I was a student. It still does, but not so much.

Riley has constructed In C so that the artistic responsibilities of the conductor - plus a large chunk of the composer's job as well - are distributed among all the players. His simple rules allow great freedom to be spread among many equal participants.

The performers stay together by listening to a steady pulse instead of by watching a conductor. This is not unlike playing with a metronome. Each player makes a continuous stream of artistic choices, unprecedented freedom for an orchestral musician. Riley stresses that all the players must listen carefully to properly fulfill their responsibilities. Their decisions matter to the final result.

Using only musical notes and musical structures In C eloquently speaks against the orchestral chain of command. It's my hope that performances of In C preserve and promote these laudable political and social principles.

These days In C has a certain dated sixties aura of utopian hippy anarchist communes about it. Cool, huh? There's no reason that feeling can't invade the world of classical music once in a while.

Very large ensemble performances of In C, which are often the very high profile ones as well, seem to lose this political message. The argument is made that some hierarchy must be introduced to avoid cacophony.

A recent celebration at Carnegie Hall celebrated the 45th anniversary of In C's composition with a large ensemble (about 70 players) which, according to the N.Y. Times, was led by a:

“flight pattern coordinator,” [who] used flash cards and hand signals to shape the sprawl.Mark Swed, in his review of a performance by 124 musicians from CalArts (at Disney Concert Hall in 2006) wrote:

David Rosenboom, the violist on the historic first recording of the piece, conducted. ... Rosenboom more carefully molded it, indicating when sections should begin changing figures lest so large an orchestra seem chaotic. ... When the longest and most harmonically complex figure (No. 35) dominated, Rosenboom emphasized the brass, and the score sounded like the end of Wagner's "Das Rheingold" writ large and Postmodern.In 2000 Michael Tilson Thomas conducted a performance by the San Francisco Symphony to which anyone could bring an instrument and join in. Sarah Cahill, in her review of the concert, wrote:

His actions were absolutely antithetical to the democratic concept of the piece.Instead of using conductors or flight controllers or referees to control a too-large group, wouldn't it be simpler to find a solution which respects the essential "every player is equal" theme. You could tell all the players to limit their playing by a certain percentage. If the number of musicians is double the optimum number, tell them to play only half the time. Simple. Even simpler: if you insist on doing this piece with too many players, you should be prepared to accept chaos. What's wrong with a little chaos? Either way, the decision of who-plays-when remains an egalitarian one. Each member of the ensemble gets an equal say and the social statement of In C, the part I find meaningful, is preserved.

I fantasize that someday In C will be programmed on regular orchestra concerts. Yes, getting this piece into the standard repertory is a long ways off. If it happened, In C would change from a "minimalist classic" into an actual piece of classical music. That would provide strong evidence that classical music has some life left in it.

I fantasize that someday In C will be programmed on regular orchestra concerts. Yes, getting this piece into the standard repertory is a long ways off. If it happened, In C would change from a "minimalist classic" into an actual piece of classical music. That would provide strong evidence that classical music has some life left in it.A chamber orchestra would be just the right size. Before the intermission the program could be, maybe, a Rossini overture and a Mozart concerto. And the second half would be a 35-minute performance of In C employing all the performers from the first half. Great concert! Of course, during In C the conductor should sit in the ensemble and play an instrument, provided he or she is capable. Otherwise tell the conductor to sit in the audience.

Now in 2009, with the history of minimalism nearing an inevitable end, conventions held, books published, courses taught, I can see how unique In C really is. Other orchestral music of recent decades has remained complex and hierarchical by comparison. No tradition of ultra-simplicity has appeared among other composers. Quite the opposite. Nothing about orchestra music - or music composition in general - challenges the structure of society. Quite the opposite.

By its very uniqueness and originality, In C deserves to be widely performed and discussed. It could easily be added to the classical canon. That revered list of works would benefit from adding this bright spot of sixties counterculture to the morass of 19th century romantic orchestral muck.

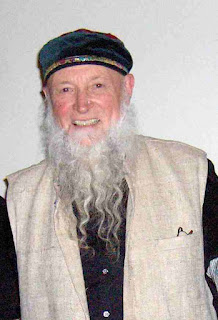

Here's an LA Weekly interview with Terry Riley.

Listen to WNYC's New Sounds show, interview with Terry Riley and David Harrington.

A print interview entitled "A Stoned Mozart?" with Terry Riley and David Harrington

You can read chapter one of Robert Carl's book here. For me, re-reading it made me want to relisten to the original recording of In C. I hadn't heard it in a very long time. But I couldn't find my LP from back in the Seventies. My friend Paul Bailey once told me that it wasn't a good performance. I scoffed. I ordered another LP via the Internet, an LP rather than a CD so I could hear the whoosh - the electronic sound which abruptly reminds you to turn the record over. I listened to it once. Paul was absolutely right - the performances sucks. You can listen to two recent chamber performances led by Paul here.

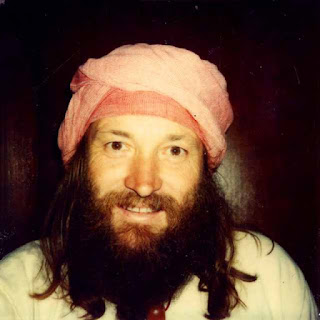

I performed In C many times, including at one particularly memorable I.C.A. concert in 1978 with the composer himself in the ensemble.

Other Mixed Meters attacks on the classics:

- Everybody Loves Beethoven (Probably) - a classical composer name recognition poll

- One Goldberg Equals Twelve Abbas - a scale to measure how interesting music is

- A Fine Line Between Classical and Parody - Musical Offsets; Wanted & Unwanted Music; Glenn Gould on Petula Clark

- Me and Mahler, Me and Iowa - How I outgrew Mahler's music

- Combining Four Letter Words: Oboe + Blog - Dies Irae and Hip Hop

- A New Rhapsody in Blue - yes, with actual improvisation

- If Music Be The Food of Love - which musics are dead, which are just dying

- David Ocker, Boy Music Critic - can't get enough Domenico Scarlatti

- The Docker Award for Mainstream Avant Garde Music - BBC Orchestra plays Cage badly

- Paradise, Pomp and Puppets - the LA Phil, Hungarian Radio Orch. and Berkeley Symphony perform music by Frank Zappa

- Mingus Epitaph - how jazz became classical one night at Disney Hall

- Sonata Heaven - about sculpting music out of the sounds all around you

A Harvard Business School study looked at job satisfaction. Orchestra players came just below prison guards. Chamber musicians came in at number 1. What’s the difference? The presence of a conductor. Conductor Ben Zander quoted here.

4 comments :

I agree with you fully that the piece does not need a conductor. I absolutely hated the Redcat performance except if i thought of it as representing the fascism of the Bush Era in all its glory. It managed that by preventing the piece to breathe and flow just what the US is like now.

Perhaps we need to twist it the other way and do Wagner without a conductor or at least Stockhausen's Ylem where the condutor's role is absurd.

I do not believe there is ever anything like a benevolent dictator.

I think Terry Riley's In C should be accepted as classical music. It's time.

I know Your post is an old one, but I just wanted to say thank you.

Your review is really interesting, and I will read your other post for sure.

cheers !

Hello person with a polychaete for an avatar -- Do I know you?

--David's wife, Leslie Harris (Polychaete Collection Manager, NHMLAC)

Post a Comment