Badmouthing their own Festival's artistic hero, Richard Wagner, probably made the job of introducing new listeners to his Ring Cycle more difficult. But as Ring Festival LA "leader" Barry Sanders said "We're not putting lipstick on a pig in this thing."

As a thought experiment, imagine how our contemporary musical world might be different today if Wagner had not hated Jews and instead had been Jewish himself. Science fiction authors indulge in this sort of imagination all the time. It's called Alternative History.

Had Wagner been born into a 19th-century German Jewish family he could well have had to convert to Christianity in order to have a successful career as a composer. After his death he would not have inspired Hitler but instead been rejected by him simply because of his Jewishness. This would have been true even if Wagner had composed the same identical operas.

Under the Nazis Wagner's music would have inevitably suffered the same fate as that of other Jewish composers. It would have been completely banned. It's even possible that today, in 2010, endless Wagnerian potboiling would have come to represent anti-Nazi resistance and maybe even gotten him included in L.A. Opera's now concluded Recovered Voices series which seemed to specialize in certain Jewish composers who wrote like Wagner.

Like all good premises for a book of alternative history this one might begin with a grain of truth. Wagner himself wondered if he was actually of Jewish ancestry because he suspected that his stepfather, who could have been Jewish, was really his biological father.

Here's a quote from an article by Derek Strahan:

The question arises: was Wagner Jewish ? Or, to be more accurate in terms of the facts, did Wagner think he might be Jewish? Or, to be even more specific, did Wagner think he might be of Jewish descent? From which arises the even more germane question, was Wagner afraid that he might be thought to be Jewish? While the probable answer to the latter question is "yes", a definite answer to questions relating to his parentage could only be provided by conducting a DNA testingWe may well believe that Richard Wagner, author of self-serving diatribes against Jewish composers of his time, poster boy for German music under the Nazis, poster boy for anti-Semitism-forgiven by people who like his music in contemporary Los Angeles, might have believed that he himself was actually a Jew. He certainly would not have wanted that to become public knowledge.

Such self-doubt must have been unbearable for him. Did he live an agonizing double life, constantly in fear that he might be discovered? Did he rationalize his baser personality traits - for example his adultery - on unavoidable Jewish character flaws? It must have been hell being Richard Wagner.

You may wonder how a person who imagined he might be Jewish could write such anti-Semitic tracts as Wagner did. It turns out that even real Jews can be anti-Semitic. These people are called "Self-Hating Jews".

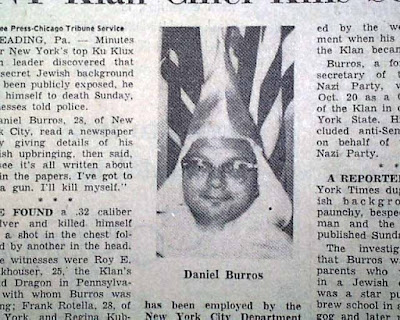

One notable self-hating Jew was Daniel Burros, a New Yorker who for a time belonged to George Lincoln Rockwell's American Nazi Party. Later he joined the KKK where he rose to the rank of Kleagle (a more interesting job title than "leader"). In 1964, when Burros was publicly outed as a Jew by the New York Times, he committed suicide. Reportedly he did this while listening to the music of ... (wait for it) ... Richard Wagner. How poetic.

Did Wagner's imagined Jewishness have any effect on his music? Strahan's article suggests a few Jewish interpretations of Wagner's operas. These are just as implausible as the endless discussions of anti-Semitic elements in those same operas. To my ear there is nothing Jewish about Wagner's music itself. (If you want to imagine Jewish Wagnerian music you could listen to Mahler.)

Much to my surprise the subject of whether Wagner wrote "Jewish music" came up in a Ring Festival L.A. press release earlier this year. Here is the final paragraph from the release announcing Wagner and Anti-Semitism. This was a symposium at the Hammer Museum held on Feb. 9, 2010. No author of the release is mentioned.

Finally, can one venture to speculate about whether Wagner has indeed been, in certain ways, “good for the Jews”? That is, how have Jewish musicians, writers, and artists appropriated and deployed Wagner’s radical innovations for their own purposes, leading to otherwise unavailable transformations? (e.g., Schoenberg, as well as the various “Recovered Voices” composers – Schreker, Zemlinsky, Ullmann, Schulhoff, etc. – many of whom adored Wagner and composed very much in his wake, and used him to create “Jewish” works like Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron). Is there such a thing as a Jewish attraction to Wagner? And if so, how might we account for it? Might we even go so far as to suggest that there is something “Jewish” about his music, despite his own evident anti-semitism?I confess to being knocked off my chair the first time I read this. I wondered whether the very suggestion -- that Wagner's music was "Jewish" because several of his imitative followers were Jews -- was slyly anti-Semitic. In reality those Jewish composers had suffered because they were German Jews not because they imitated Wagner. Their Jewishness got their Wagnerian music consigned to the very backwaters of music history.

If it can be argued there was "Something 'Jewish'" about Wagner because he influenced Jewish composers, couldn't one argue that there was "Something National Socialist" about Wagner because he influenced Nazis?

I briefly wondered if Ring Festival LA endorsed this crazy idea from one of their own press releases. I also wondered if it was a troll intended to provoke an argument. I concluded that it was just pseudo-academic speculation intended to blur the real issue: whether it's okay for Wagner's fans to ignore his political influence over generations of dangerous anti-Semites. (my opinion: it's not okay.)

I didn't attend this symposium. I just discovered that the Hammer museum has provided a nearly two-hour video of the event online. In Kenneth Reinhard's introduction he vaguely echos the bizarre press release. That makes me wonder if he's the anonymous author who is suggesting that we need to discuss Wagner's Jewish music. I was happy to discover that the particular subject did not come up.

(I suggest you let the long video download completely before watching.)

I'm also happy to report that I found the seminar fascinating. The standard tropes about whether the Wagnerian plots or characters are anti-semitic got discussed (my opinion: they're not). Also much energy was given whether it's time to quit talking about the subject of Wagnerian anti-semitism (my opinion: it's not).

I was extremely impressed with the comments of Leon Botstein. In the performative sense he stole the show. Also in the informative sense. I found myself in complete agreement with a great deal of what he said. I found more agreement with his notions of Wagner's proper place in modern culture or modern Los Angeles than with anything I've heard or read on the subject for the last year. Botstein is a respected academic and talented orchestra conductor whose opinions carry a lot more weight than my own.

I'm going to close this post with selections from Botstein's opening remarks. These begin at the 40 minute mark. Clearly he was not reading from a prepared script. You'll find him much more entertaining on video.

First of all, I don't think more productions of the Ring are necessary. Not because he was an anti-Semite but because it's just boring.

I was reminded, genius that Wagner was, I'm tired of this. And I find its bombast and its inflated character hard to sit through. And I also think ... there's nothing redeeming about this work and it needs to be put to rest. There's so much more good music and good opera to be put on the stage. I don't know why people are doing this any more. ...

The only thing interesting about Wagner is the capacity to write brilliant musical prose and to repeat himself without musically losing your interest. The craft of this composer is enormous. And the innovation that he brought to the writing of music really has very few parallels in the history of music. You can't avoid him if you're a musician. But if you're not a musician I don't know what you're doing here.Hooray for Leon Botstein! Too bad that his opinions didn't get more widely reported.

You can read a dour review of the seminar here.

Here's an article about Daniel Burros and other similar cases.

A 1998 New York Times article, The Specter of Hitler in the Music of Wagner by Joseph Horowitz, speaks about Wagner's recognition of Jewish traits in himself:

If Wagner relied in practical ways on certain Jewish supporters, he also experienced a psychological dependency: the Jews embodied aspects of Wagner himself, aspects he wished to transcend and could not. The Jew in the mirror was the negative image of an unfulfilled personal identity.

A great alternative history novel -- about European Jews who settle in Alaska when the State of Israel does not survive - is called The Yiddish Policeman's Union by Michael Chabon. It's a murder mystery.

Some other Mixed Meters writings on why Los Angeles is not a Wagner town.

- Typography can remind us that Wagner was a bad guy: Wagner with an Asterisk

- How Ring Festival LA could have avoided problems: Ring Festival LA, Wrong Festival LA

- Wagnerites and Nazis march in Los Angeles on the same day: Ring Festival LA Meets Hitlers Birthday

- Wagner in the Nazi extermination camps: Ring Festival LA Begins

- One California composer's response to the Ring: Listen to Wagner's Entire Ring in One Second

- Another California composer's response to the Ring: Kenton Wagner

- Not all music was influenced by Wagner: Wagner Inspires Pop Music

- Just Say No to Drugs and Wagner: Wagner Invades Poland

- The man who couldn't make LA an opera town: Placido Domingo, High Culture Meets Pop Culture

Botstein Tags: Richard Wagner. . . Hammer Museum. . . Ring Festival LA. . . antisemitism. . . Kenneth Reinhard. . . Leon Botstein. . . Daniel Burros