At that moment I heard a little voice in my head. "You should write a blog post about Milton Babbitt and the Super Bowl." Babbitt had passed away only a few days earlier.

"But," I replied, "Babbitt has nothing whatsoever to do with professional football."

"Not my problem," it countered. I called it several unpleasant names - but the voice had already left my head.

That's how I got stuck trying to compare America's premier professor of serial music composition and America's premier professional football championship holiday. It's my brain's fault. Such an essay is uphill work because the intersection of the sets of properties of Babbitt's music and Super Bowl games is null. (Babbitt would understand. He was a brainy guy.)

I reread "Who Cares If You Listen", Babbitt's 1958 editor-titled essay in High Fidelity Magazine. He lamented the lack of contextual background which listeners brought to serious contemporary music:

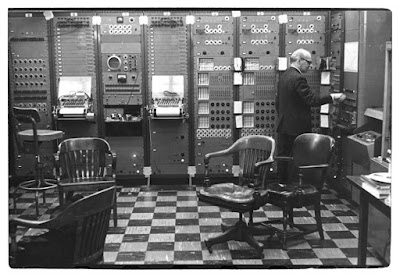

The time has passed when the normally well-educated man without special preparation could understand the most advanced work in, for example, mathematics, philosophy, and physics. Advanced music, to the extent that it reflects the knowledge and originality of the informed composer, scarcely can be expected to appear more intelligible than these arts and sciences to the person whose musical education usually has been even less extensive than his background in other fields.To Babbitt, writing music was highly technical and highly theoretical. He thought that such research would lead to future musical benefits for all. Theory and composition-wise that certainly never happened, although the miniature descendants of the room-sized synthesizer which Babbitt used in the fifties have since turned music on its head.

Babbitt concludes his essay with a reference to the "is classical music dead?" debate:

Granting to music the position accorded other arts and sciences promises the sole substantial means of survival for the music I have been describing. Admittedly, if this music is not supported, the whistling repertory of the man in the street will be little affected, the concert-going activity of the conspicuous consumer of musical culture will be little disturbed. But music will cease to evolve, and, in that important sense, will cease to live. (italics added)Here's some of Milton Babbitt's music to listen to as you read about the Super Bowl.

The Super Bowl is a battle in abstract. Two teams of armored warriors engage in ritual medieval combat while attempting to adjust the geo-position of an oviform leather ball to their own advantage. There are many ways in which the Super Bowl is different than Milton Babbitt's music.

- Milton Babbitt's music does not need a half time show. Nor is there a cuisine (e.g. pizza, wings, chips and guacamole) associated with it.

- Babbitt's music receives little, if any, attention. Super Bowl Sunday has become an important all-American celebration of capitalist sports.

- Babbitt's music is not widely known. The Super Bowl has millions of fans.

- Babbitt's music is highly intellectual. The brainiest aspect to the Super Bowl is probably chronic traumatic encephalopathy. That's the progressive damage done to the brains of players who are constantly bashing into one another with great force. This very violence is one of the reasons people like football.

- Babbitt used higher mathematics in the composition of his music. Mathematically, a Super Bowl fan must be able to add four numbers and decide whether the total is greater than ten. Extra credit is given to fans who can remember the rules for Roman numerals. This year was Super Bowl XLV.

- Listening to Babbitt's music requires intense concentration. Watching football does not require much attention span at all. The plays are short and there is plenty of time in between for commentators to explain what happened - just in case you missed something.

- Babbitt's music has little commercial value. Corporations spend millions of dollars for a few seconds of Super Bowl air time to sell their products.

Naturally I listened to some of Milton Babbitt's music before writing this. I was struck by a certain nineteen fifties feeling of his pieces, sort of like giant audible Jackson Pollock paintings. Overall, his abstraction is pure and his attention to technique is overarching. On a micro level each event, each note, each drip becomes its own world, like a tiny atom whizzing through vast emptiness. I strained (and failed) to hear connections. What's more, his notes never combine to create emotion or excitement or drama, the very things I feel music is good at. Maybe someone with better ears or more nimble brain can fathom Babbitt's music.

I also watched some of the Super Bowl broadcast. Football, like any sport, is goal oriented activity. The goal is winning and the drive towards that goal represents great drama. We can pick a side to cheer for and personally share in outcome. The competition and violence become easy metaphors for much of real life. These are amplified by the media until the whole event is larger than life. The Super Bowl is geared to producing emotion, excitement and drama - and little else.

Milton Babbitt and the Super Bowl are opposites on any spectrum. I guess the one thing they have in common is my personal failure to understand either one. I find them both empty experiences. I scratch my head because I see that other people seem to get pleasure from them. I bet there are even certain people who love both Babbitt and the Super Bowl. Why didn't the voice in my head visit them instead? Those people should have written this article.

Here's a one-hour movie entitled Babbitt: Portrait of a Serial Composer by Robert Hilferty, completed by Laura Karpman. If you're interested in the life and personality of this highly intelligent, academic, uncompromising artist, I highly recommend watching. This was more fascinating for me than listening to Babbitt's music directly.

It also reminded me of the one time I met Milton Babbitt. In the very early seventies I was an undergraduate at Carleton who had only recently decided to take a chance at a career in composition. He and I had a brief private discussion during which he was not particularly discouraging. He gave a lecture to the assembled music students and faculty - many of whom attended out of politeness more than interest.

I remember suggesting that he was a professor at Columbia (rather than Princeton) because I knew of him mostly through recordings from the Columbia Princeton Electronic Music Center. He seemed a bit annoyed at my confusion between the two schools. This movie also reminded me just how quickly he could talk.

About 52 minutes into the movie a young woman makes this comment:

My brain is stimulated by Milton Babbitt's music and my heart is touched by the freeing of my mind, which is a different way to have one's heart touched than usual. And in that way I find his music extraordinary and unique.What a beautiful sentiment. I wonder what she'd have to say about the Super Bowl.

ADDENDUM: okay, here's one way in which serial music composition and professional football are alike: they're both activities of interest principally to men.

Milton Bowl Tags: Milton Babbitt. . . Super Bowl. . . serial composition. . . professional football

1 comment :

"ADDENDUM: okay, here's one way in which serial music composition and professional football are alike: they're both activities of interest principally to men."

This is also what football & Milton Babbitt have in common with the Three Stooges.

SF

Post a Comment