I am offering two recordings of the music of John Cage. Both were performed in Los Angeles in the early 1980s on concerts produced by the Independent Composers Association. I no longer remember exactly why I saved these cassette recordings. Subconciously, I guess, I knew that I would need material for my blog one day, once my hair turned gray.

Both concerts were apparently reviewed by the L.A. Times although I don't have access to either article nor to concert programs. I do remember that the reviewer remarked how Atlas Eclipticalis felt like the 'classical' work on a program of modern music. Imaginary Landscape was part of a tape music concert which also included pieces by Scott Fraser, Luc Ferrari and Jonathan Harvey.

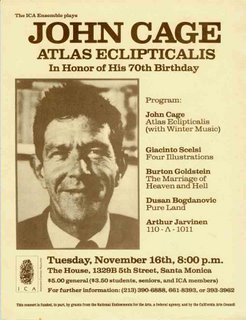

listen to John Cage Atlas Eclipticalis with Winter Music - 1756 seconds - November 16, 1982 - The House, Santa Monica, California - The Independent Composers Assn. Ensemble, Delores Stevens, pianist, Stephen Mitchell, conductor

listen to John Cage Imaginary Landscape #4 with Radio Music - 497 seconds - May 21, 1983 - Stella-Polaris Gallery, Los Angeles, California - The Independent Composers Assn. Radio Ensemble

(Read about: why I have this flyer and how I know the other composers on the tape concert. At some point I made a copy of the Atlas Eclipticalis tape at half speed. I much preferred listening to it that way.)

As someone whose musical thinking was greatly influenced by Cage's work and ideas, I would be remiss to let this occasion pass without comment. On the other hand, these days I'm really more interested in observing how Cage is being remembered by the classical music establishment than I am in the man or his music.

I see Cage as the ultimate 20th century iconoclastic artist, someone who smashed the sacred ideas of the music world. In their place he brilliantly offered indeterminacy, new performance techniques, electronics, wildly inventive compositional systems and a sense of calm, unflappable, detached theatricality. He leavened this mixture with a galaxy of personal anecdotes, ideas from Zen teachings, mycology and the force of his own personality.

Indeed, I believe that the man himself sets Cage apart from the other composers of his time. He injected himself uniquely into his music by performing, lecturing or just being charming. In his second hundred years how essential will his persona be to the continued acceptance of his music? Eventually everyone who directly knew and revered Cage will be gone. Time will tell us if his music alone will continue to inspire new listeners. Or maybe his writings and ideas will motivate future generations to become fans.

In the coming decades the ears of the audience will, no doubt, continue to blend the music of the entire post-World War II avant-garde into a more homogenous musical experience. Although there will be plenty of academic types to make plenty of fine distinctions, it will be harder and harder for more casual listeners to choose sides in those ancient artistic conflicts. Total control via serialism or total randomness using chance operations? As it turned out, the aesthetics were much the same either way.

The centennial celebrations are heavy with the idea that Cage was a strong artistic wind that will blow through the ages. I suppose it is possible that Cage, by the year 2112, could land a spot in the pantheon of the greatest dead white male composers. Even so "Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner and Cage" would be quite a stretch. I wouldn't be surprised if he comes to be regarded as the essential 20th century serial composer, eclipsing all those famous Europeans and academic Americans of the last fifty years.

Cage made a big deal out of studying with Schoenberg - and spent much of his later career trying to curry the approval of his long-dead teacher. Here's an excerpt from a fascinating L.A. Times article by Mark Swed about Cage's early life in Los Angeles:

Still the young composer continued to, as he put it, worship Schoenberg like a god. He took away from Schoenberg the idea that a composer always needed some kind of system. And Cage always came up with one.Schoenberg would likely have said that music needs more than a system of rules. I'm pretty sure he would have insisted that music also requires meaning and expression.

Recently, in a BBC interview with Norman Lebrecht, John Adams talked about John Cage (This is from the 9/3/12 podcast, starting about 15'48")

Actually there was a four or five year period when I was not that cognizant of minimalism. I was a real acolyte of John Cage. . . . I knew all my John Cage very well and I was very deeply imbued in John's orthodoxy. I do think that Cage is a very orthodox composer. That surprises people because they think of him as an iconoclast but he actually is a strangely intolerant composer in a certain way, when it comes to anything which doesn't fit into his very precise world. That means most of western music whether it's Miles Davis or Beethoven. Eventually I just had to throw that out. Because I had fun doing John Cage and you could talk about it forever but my background and my musical breeding had brought me up to love great music. Also I keep going back to this experience about music is essentially the art of feeling and Cage had no place in that.(Here's a fun anecdote about Cage's intolerance.)

We can argue later about what Cage is and what Cage is not. After that we can take a swing at what is great music and what is not. Or we can just agree to disagree.

Right now the question I am more interested in is 'How will perceptions of Cage change over time?' The best way to find out is to simply wait and see. It's more fun to guess.

I expect that the great iconoclast will gradually be transformed by his remaining acolytes into a great icon. He will be revered, Zen-like, in concerts and concert halls. Cage, I'm sure, would have liked nothing better. I also expect that the manner in which his music is performed will become increasingly conventional and prescribed. That's sad, but it is the way of what we call classical music.

Personally, the harder it becomes to experience the music of John Cage on a street corner, the more we will lose what I think is the real value of his work and life.

As John Cage has said, music is all around us if only we had ears. There would be no need for concert halls if man could only learn to enjoy the sounds which envelop him, for example at Seventh and Broadway at four p.m. on a rainy day.(That quote comes from the spoken introduction to the 1970 Everest recording of Variations IV by John Cage.)

(Seventh and Broadway: 1 2 3 4 5 6)

Random Tags: saintdom. . . opposition. . . podgy. . . laburnum. . . exclamation. . . gargoyle

2 comments :

I have never thought of you as a composer influenced by Cage. But then again it might be like his effect on me more in the terms of sound than process. While it s true that we have this sound all around us to listen to and enjoy, if given the option of giving up that sound or what is called music, i would give up the former.

I carefully wrote only that my "musical thinking was greatly influenced". It started when I read Silence in college and then studied with Earle Brown at CalArts. I was fascinated with these notions, but not so much with the sound of Cage's music.

I wrote quite a few open form pieces in which I controlled the content but allowed it to be ordered or layered in different ways. My current Seasons series has that notion, the various sections are intended to be combined by the listener including with other music. These days that idea sounds lots less "Cagean" than it did 30 years ago.

And then there's my Starbucks Music Mask which does work remarkably well when listened to on an iPod to eclipse annoying conversations, muzak and environmental noise. That has a Cagean element which I find particularly practical.

Post a Comment