RING FESTIVAL LA PLUS THREE

In November 2008 Placido Domingo announced:

“Ring Festival LA will be a defining moment in the cultural history of Los Angeles.”Read the whole initial press release here. The festival happened in 2010. Read more about it here.

At this point I think we at Mixed Meters (we in this case being the euphemism for me, David Ocker) are the only ones who think about this subject any more. And it's entirely possible that I'm the only person who had any sort of defining moment as a result of their festival, as it got me interested in the relationships between Hitler, the Nazis, Wagner and his endlessly turgid music.

Last December the LA Times reported that LA Opera had paid off the $14,000,000 loan which squeaked them through their Ring cycle production. That loan was controversially co-signed for by the nearly 10 million residents of Los Angeles County thanks to the actions of our 5 elected Supervisors.

Since their go-round with Wagner LA Opera has been sticking with crowd-pleasing opera classics. Although next year they will dip their toe into living memory by presenting Philip Glass's 1976 Einstein on the Beach. My late 70's self would be thrilled. My current self thinks Einstein is probably somewhat less boring than Wagner but still not worth sitting through. (Addendum: they're also doing Billy Budd, premiered when I was three months old.)

Here's a cartoon to lighten the mood.

THE RING OF MYTHS - WAGNER: BANNED IN ISRAEL

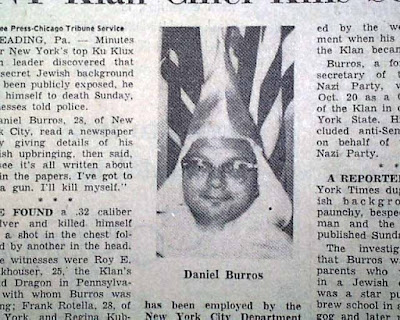

In the endless discussion of why Wagner was such a creep, a prime topic is his anti-semitism. Of course the extreme anti-semitism of his descendants and their support of Wagner's most influential and anti-semitic fanboy, Adolph Hitler, come up repeatedly.

Often one of the talking points in these discussions is the unofficial ban on the music of Wagner in the nation of Israel. This subject still hits the news periodically. I mentioned a development in my LA Ring Festival 2-year memorial. The ban dates from November 12, 1938 when conductor Arturo Toscanini removed the overture to Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg from a concert by the Palestine Symphony Orchestra to protest the Nazi-organized anti-Jewish riots known as Krystallnacht three days earlier.

A fascinating book published in 2001 details the history of this ban: The Ring of Myths, The Israelis, Wagner and the Nazis by Na'ama Sheffi.

Interesting facts abound. For example, right after the war any music with lyrics in the German language, even works by Mahler, was deemed unsuitable by the public. The music of Richard Strauss was banned along with Wagner's (although unlike Wagner it has since achieved greater acceptance). In 1953 Jasha Heifetz was physically attacked and slightly injured by a man wielding an iron pipe. His motive? The violinist insisted on playing a work by Strauss in Israel.

Throughout The Ring of Myths prominent musicians paternalistically promote adding Wagner's music to the Israeli concert repertoire despite knowing there will be strong public opposition. Zubin Mehta and Daniel Barenboim, I'm talking about you. Their excuse is that Wagner is somehow essential to music history or orchestral technique. This line of reasoning rings rather hollow in my ears - but my readers probably already know what I think of Wagner's music.

Sheffi does her best to help an outsider keep Israeli politicians, political parties and newspapers, across the entire spectrum from left to right, straight. Uphill work! Because most of the primary sources of this story (like newspaper articles and the archives of the Israel Philharmonic) are all written in Hebrew, this book gives a non-Israeli a chance to follow what would otherwise be a closed discussion.

The Ring of Myths clearly shows that the reasons for continuance of the Wagner ban have changed over time. In the early years of the state of Israel anything even remotely connected to Germany would be protested. As the relations between Israel and Germany improved (often represented by Israelis driving Volkswagens or Mercedes), Richard Wagner continued as an emotionally-charged symbol of the Nazis. This emotion repeatedly got caught up in the arcane ebb and flow of Israeli politics. In Israel, of course, religion colors most political debates.

Sheffi succinctly outlines these shifts in her preface:

In the 1950s and 1960s Wagner was an important argument for the factions opposing the restoration of ties with Germany; in the 1970s he was a vehicle for the anger of intellectuals at what they termed Israeli hypocrisy; in the 1980s he was a key figure in the struggle over the preservation of the memory of the Holocaust; and in the 1990s he served the national ultra-Orthodox religious ideology, which calls on Israelis to content themselves with Hebrew culture and stop copying the ways of the gentiles.The last stage was most interesting to me since I often think that classical music has become a kind of religion for certain people. This is most obvious in the cult-like behavior surrounding Richard Wagner's music. People who argue in favor of Wagner seem to do so based on their deep personal, emotional belief in the power of his music. This primary dogma informs each new debate in a logically unassailable manner. Such fundamentalism is, in my opinion, just as basic to most organized religion as it is to Wagnerism.

Sheffi ultimately argues that Israelis can and should find better ways of commemorating the Holocaust than by symbolically banning Wagner. Maybe. I think that as a symbol Wagner is permanently stained by Nazism, just as the swastika has been. Wagner and his music will continue as a symbol of Hitler and the Nazis for a long time to come.

WAGNER AND STEPHEN FRY

Stephen Fry, a famous English actor, is a Jew. Some members of his family perished in the Holocaust. Fry is also a big fan of the music of Richard Wagner. He has explored the resulting existential tension in a movie entitled Wagner and Me.

It opens on a rehearsal of the Prelude to Act 3 of the opera Siegfried and then cuts to scenes of Bayreuth Germany home of the infamously famous Bayreuth Festival founded by and dedicated to Wagner himself.

Fry's narration, often exited, breathless, even awestruck, takes an immediate stab at explaining why this place is so important:

Well, for anyone who loves Wagner as I do this place is Stratford-upon-Avon, Mecca, Graceland all rolled into one.Yep. Fry's description of this shrine puts Wagner on the same level of not just great artists like Elvis Presley and William Shakespeare, but right up there with an actual religious prophet worshipped by a billion and a half people. I keep sayin' - Wagner is a religious thing.

At first Fry wanders aimlessly around the Festspielhaus like a kid in a candy shop, gleeful, astonished and amazed by the smallest things because everything he sees or touches has some connection to Wagner. He says "Oh, I wish I were a Valkyrie sometimes."

Then, standing in a hallway hung with pictures of conductors (we are shown Hermann Levi, about whom Wagner might have said "some of my best friends are Jewish") Fry gets around to explaining why he likes Wagner's music.

I must have been 11 or 12 when I first heard Wagner's music on my father's grammophone. It was the overture to Tannhäuser one of his earlier operas and it did something most extraordinary to me. I've always loved music. I've always been hopeless at performing it, couldn't really play an instrument, certainly can't sing, but it's made me do things inside. It's released forces within me. And no music has done it like Wagner's.Later he refers to Wagner's music as "gut-wrenching", but I don't think those are the internal forces he has in mind. Blessedly, Fry never tries to project his Wagner epiphany on other people. Although he revisits the "it does things to me" theme, he keeps the revelations personal throughout the movie at least until the very end. Fry continues:

To experience the music I love in the composer's own theater is something I've dreamed of doing for as long as I can remember. But it's no secret that my passion was also shared by Him.

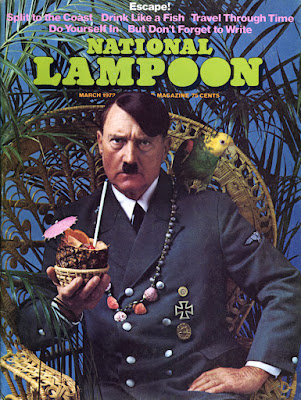

"Him" (Fry intones "Him" dripping in villainous overtones) is Hitler who pops up on the screen just at that moment, shown seig heiling from a window of Bayreuth

And like me he felt the magnetic pull of Bayreuth. I'm Jewish and lost relatives in the Holocaust so before I take my seat in the Festival House I need to feel sure I'm doing the right thing.Fry drops back from this ominous foreshadowing and gives us fine little essays about Wagner's biography and why his music is important plus some clips of opera productions. He meets Wagner's great-granddaughter, has a piano lesson on the Tristan chord, travels to Russia. The photography of beautiful scenery, ornate opera halls and fairy-tale castles is exceptional. Eventually he gets back to the Hitler question in two interviews.

One is with Dr. Joachim Köhler, author of a controversial book Wagner's Hitler, The Prophet and His Disciple. They talk in the Nuremberg stadium where the Nazi rallys were held (think Triumph of the Will) and then Fry reflects alone on the Wagner/Nazi connection.

I suppose I think of it like this, imagine a great beautiful silk tapestry of infinite color and complexity that has been stained indelibly. It's still a beautiful tapestry of miraculous workmanship and gorgeous color and silken texture but that stain is real and I'm afraid Hitler and Nazism have stained Wagner. For some people that stain ruins the whole work. For others it is just something you have to face up to.

Later he talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, a cellist who survived the Auschwitz concentration camp because of her musical abilities. He asks her "Am I betraying my Jewishness by playing Wagner and liking him?". Her answer:

I think everybody has to come to terms by themselves. I would never forbid anybody to listen to Wagner. If it was the music without the drama one wouldn't probably argue with it. But apart from the fact I would never have the patience to sit for 5 hours and listen to so much noise.And, at the end, of course, Stephen Fry decides that indeed he can listen to Wagner at Bayreuth, that he can ignore the stain and that he is doing the right thing. We see him, ticket and pillow in hand, eagerly entering the concert hall for opening night at Bayreuth. And we should forgive him his besotted love of Wagner's music because he did ask the hard questions and faced up to the negative associations directly.

Finally he tells us that, if we've never heard it before, we should give Wagner's music a try. He concludes:

I still believe, as firmly as I believe anything, that his work is important and is on the side of the angels. It is fundamentally good.Yes, it comes down to a matter of belief. He believes in Wagner the same way people believe in imaginary gods. You accept the faith or you don't. I think Mr. Fry is to be commended for not whitewashing the bad parts of his story but he completely fails to explain, exactly, what is so good, so angelic about Wagner or his music. (Granted, he does explain why Wagner is so important. Even I agree that Wagner is important. I just wish he could be made less so.)

In the final analysis, you listen to this music and it does something inside of you, something gut-wrenching, or it doesn't. That reaction - or lack of it - seems to determine your attitude towards Wagner and his music, probably for the rest of your life. More than that, unless you were a Holocaust survivor, a person's attitude towards the music further seems to determine one's outlook on how Hitler manipulated Wagner as a symbol. The entire topic has been reduced to dogma and symbols. And just like in religion, a believer either has to accept the dogma and venerate the symbols or stay out of the church.

Previously I've written a lot about these subjects. Here are links which will show articles marked with these tags:

Ring Festival LA

Richard Wagner

Hitler and Nazis

Naturally, there's a lot of overlap.

The most cogent discussion of Wagner's music in contemporary culture was a lecture given by Leon Botstein as part of Ring Festival LA at the Hammer Museum. (Skip to about 40 minutes.) This was discussed in the MM post Suppose Wagner Had Been Jewish.

Beating a Dead Horse Tags: Richard Wagner. . . Ring Festival LA. . . Na'ama Sheffi. . . Stephen Fry

.jpg)