Sometimes I have to wait for the forgetting before I consider a work to be finished. It took almost one year for Summer 2014 from my The Seasons to be sufficiently forgotten. I no longer remember precisely why I was unhappy with it.

When I finished composing it on September 22, 2014, I decided it needed revisions. I listened to it every few months. I was less unhappy with it each time. Eventually I realized I no longer wanted it hanging over my head. After a while it seemed okay, I guess. Good enough. It is what it is. No worse than my other music. Better than some.

So this summer (the one in 2015) I mixed the tracks and produced an audio file. Now it's available online and you can listen to it and I can attempt to forget it again.

The conceit of composing The Seasons is that I write a little bit of music for each day of the calendar. I try to actually write one every day. The mistake I made with this piece, I think, is that I had too many ideas upfront about what I would compose.

This daily composing scheme seems to produce better results if I just make sure each segment flows out of the previous day. Occasionally I check to make sure each week hangs together. When I try to make grand overall form or concept ahead of time, the way I was taught back when I studied composition, trouble ensues. I'm not that kind of composer.

The grand form I imagined this time was a finale to a five-movement romantic symphony. Mahler's Seventh would be a good example. Mind you, I would not be writing grand romantic five-movement symphonic music. Instead I would merely hint at the overall form of a five-movement symphony. Each movement would be one season. I would call it The Five Seasons - going Vivaldi one better. I'm still going to call it that.

The five movements, composed in consecutive seasons, are:

- Caprice (Summer 2013, short version) (June 20, 2013 through September 21, 2013)

- Nocturne (Autumn 2013, short version) (September 22, 2013 through December 20, 2013)

- Allegro (Winter 2013, short version) (December 21, 2013 through March 19, 2014)

- Minuet (Spring 2014, short version) (March 20, 2014 through June 20, 2014)

- Finale (Summer 2014, short version) (June 21, 2014 through September 22, 2014)

I hatched this plan about the time Minuet completed. At that point, early June 2014, I envisioned the last season/movement would be a loud bang-up conclusion. I had already given the four seasons single word musical terms as titles so the name Finale sprang easily to mind. I set out to write music which rushed headlong to an obvious, inescapable and completely blatant final chord. I wanted an ending no one could miss.

Yeah, it does that.

Yeah, there's more.

I decided the music would be based on a fragment from the Egmont Overture by Ludwig van Beethoven. In the five movement form this would balance the first movement written in Summer of 2013. I called that one Caprice because it is based on the 24th Caprice by Nicolo Paganini. Formal structure, huh?

The Beethoven and Paganini pieces were written at approximately the same time (roughly 200 years ago) and both inspired compositional ideas in the student me decades ago. It has taken me more than 40 years to get around to using these ideas. I'm old now and I'm allowed to dig around in my past without good reason. I must have had lots of other ideas back then as well. These two were never forgotten.

I remember that the Beethoven idea happened in a momentary flash the very first time I heard the Egmont Overture. I was in college, studying classical music and hearing recordings of famous repertoire for the first time. It happened at a specific point in the music, let's call it the "inspirational moment", not too far from the end, at bar 309 to be precise.

First you hear this theme (measure 307-8):

Then, immediately, this happens:

This was not at all what I was expecting. I was really surprised. "Whoa," I thought, "how did Beethoven think of THAT?" It happens so fast there wasn't enough time to wonder exactly what I did expect.

I began to ponder Beethoven's brain. (Here's a picture of what might be Beethoven's skull.)

Specifically I pondered how he got from the first idea to the second. I decided it might be interesting to explore that briefest of moments. Essentially I was interested in what happens exactly at the barline between measure 308 and measure 309. Barlines are silent things. They happen between sounds.

I decided to use this mere instant, the "inspirational moment", to generate a piece of my own. It wasn't the themes that interested me. I was interested in those mere milliseconds of time during which the idea seems to be created.

I have no idea how, in reality, Beethoven came to juxtapose those particular musical ideas. Nor do I much care. He probably worked hard at it. If you're interested I suggest you ask your Doctor of Musicology.

Initially I imagined a minimalist process piece, beginning with the eight-note theme repeating over and over. And over. Repeating things over and over was a radical idea back then. Slowly and imperceptibly the music would evolve into the second theme. Somehow my music might reveal Beethoven's thought process.

Had I actually accomplished this, the piece could have been inserted directly into Ludwig's original overture right at the "inspirational moment". Beethoven time would suddenly stop and the listener would be hurled deeply into the workings of my brain. Eventually things would return to the Beethoven brain exactly at the same point where I took over. Egmont Overture would then continue as if nothing unusual had ever happened.

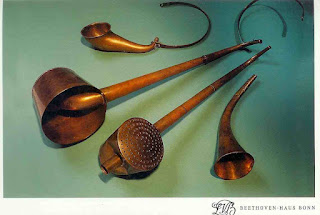

Does this remind you of every movie about a time machine ever? (This is Beethoven's death mask.)

I never pursued the idea. Decades passed. However, each time I heard the Egmont Overture I remembered my unfinished idea. There could be no forgetting because Egmont is a stirring, heroic concert opener and it gets programmed. Apparently classical concerts need stirring, heroic concert openers.

Finally on or about Saturday, June 21, 2014, the date I began Summer 2014 from The Seasons, I decided it was high time to try putting paid to this idea once and for all. I began to incorporate the eight-note theme into the daily fragments.

And of course, the final result of Finale (Summer 2014 short version) bears only a small resemblance to what my imagination was predicting on June 21, 2014. Finale does end definitively. I got that right. There is a lot of Beethoven worked into it. I got that right as well. Even the "inspirational moment" happens in my piece just as it does in Beethoven's.

And, as you remember from the beginning of this post, I was never happy with the result. It's different than whatever it was I had set out to write. Oh well, it is what it is. No worse than my other music. Better than some.

Finale is completely, totally different than the original idea I imagined as a student. I have not put paid to that idea. In reality I doubt I could have made an interesting piece, either back then or right now. I wonder if anyone could, especially without being totally pedantic and boring.

Unfortunately I have made forgetting my idea more unlikely than ever. I will remember it because now there are two pieces, one by Beethoven and one of mine, that will remind me of how I failed to follow through.

click here to hear Finale (Summer 2014, short version) by David Ocker - © 2015 David Ocker, 720 seconds

You might be interested in the long version (fragments with silences) of Summer 2014 (4106 sec.): [listen] [read]

In a hurry: listen to Garbage Days of Summer 2014 (133 sec.): [listen] [read]

Here's another piece of mine that required two years of forgetting.

Here are all Mixed Meters posts about poor old Ludwig van Beethoven.

Here's a video of facial reconstruction of Beethoven's face based on his death mask (shown above).

If you must know, the "inspirational moment" in Finale happens at 8'19". And if you insist on skipping ahead and listening to only that one spot, please do me this favor: leave a comment saying how much you enjoyed the entire piece, even though you only listened to a few seconds. Just lie about it. That seems fair.

Yeah, there's more.

The Beethoven and Paganini pieces were written at approximately the same time (roughly 200 years ago) and both inspired compositional ideas in the student me decades ago. It has taken me more than 40 years to get around to using these ideas. I'm old now and I'm allowed to dig around in my past without good reason. I must have had lots of other ideas back then as well. These two were never forgotten.

I remember that the Beethoven idea happened in a momentary flash the very first time I heard the Egmont Overture. I was in college, studying classical music and hearing recordings of famous repertoire for the first time. It happened at a specific point in the music, let's call it the "inspirational moment", not too far from the end, at bar 309 to be precise.

First you hear this theme (measure 307-8):

Then, immediately, this happens:

This was not at all what I was expecting. I was really surprised. "Whoa," I thought, "how did Beethoven think of THAT?" It happens so fast there wasn't enough time to wonder exactly what I did expect.

I began to ponder Beethoven's brain. (Here's a picture of what might be Beethoven's skull.)

Specifically I pondered how he got from the first idea to the second. I decided it might be interesting to explore that briefest of moments. Essentially I was interested in what happens exactly at the barline between measure 308 and measure 309. Barlines are silent things. They happen between sounds.

I decided to use this mere instant, the "inspirational moment", to generate a piece of my own. It wasn't the themes that interested me. I was interested in those mere milliseconds of time during which the idea seems to be created.

I have no idea how, in reality, Beethoven came to juxtapose those particular musical ideas. Nor do I much care. He probably worked hard at it. If you're interested I suggest you ask your Doctor of Musicology.

Initially I imagined a minimalist process piece, beginning with the eight-note theme repeating over and over. And over. Repeating things over and over was a radical idea back then. Slowly and imperceptibly the music would evolve into the second theme. Somehow my music might reveal Beethoven's thought process.

Had I actually accomplished this, the piece could have been inserted directly into Ludwig's original overture right at the "inspirational moment". Beethoven time would suddenly stop and the listener would be hurled deeply into the workings of my brain. Eventually things would return to the Beethoven brain exactly at the same point where I took over. Egmont Overture would then continue as if nothing unusual had ever happened.

Does this remind you of every movie about a time machine ever? (This is Beethoven's death mask.)

I never pursued the idea. Decades passed. However, each time I heard the Egmont Overture I remembered my unfinished idea. There could be no forgetting because Egmont is a stirring, heroic concert opener and it gets programmed. Apparently classical concerts need stirring, heroic concert openers.

Finally on or about Saturday, June 21, 2014, the date I began Summer 2014 from The Seasons, I decided it was high time to try putting paid to this idea once and for all. I began to incorporate the eight-note theme into the daily fragments.

And of course, the final result of Finale (Summer 2014 short version) bears only a small resemblance to what my imagination was predicting on June 21, 2014. Finale does end definitively. I got that right. There is a lot of Beethoven worked into it. I got that right as well. Even the "inspirational moment" happens in my piece just as it does in Beethoven's.

And, as you remember from the beginning of this post, I was never happy with the result. It's different than whatever it was I had set out to write. Oh well, it is what it is. No worse than my other music. Better than some.

Finale is completely, totally different than the original idea I imagined as a student. I have not put paid to that idea. In reality I doubt I could have made an interesting piece, either back then or right now. I wonder if anyone could, especially without being totally pedantic and boring.

Unfortunately I have made forgetting my idea more unlikely than ever. I will remember it because now there are two pieces, one by Beethoven and one of mine, that will remind me of how I failed to follow through.

click here to hear Finale (Summer 2014, short version) by David Ocker - © 2015 David Ocker, 720 seconds

You might be interested in the long version (fragments with silences) of Summer 2014 (4106 sec.): [listen] [read]

In a hurry: listen to Garbage Days of Summer 2014 (133 sec.): [listen] [read]

Here's another piece of mine that required two years of forgetting.

Here are all Mixed Meters posts about poor old Ludwig van Beethoven.

Here's a video of facial reconstruction of Beethoven's face based on his death mask (shown above).

If you must know, the "inspirational moment" in Finale happens at 8'19". And if you insist on skipping ahead and listening to only that one spot, please do me this favor: leave a comment saying how much you enjoyed the entire piece, even though you only listened to a few seconds. Just lie about it. That seems fair.